3. The Skull

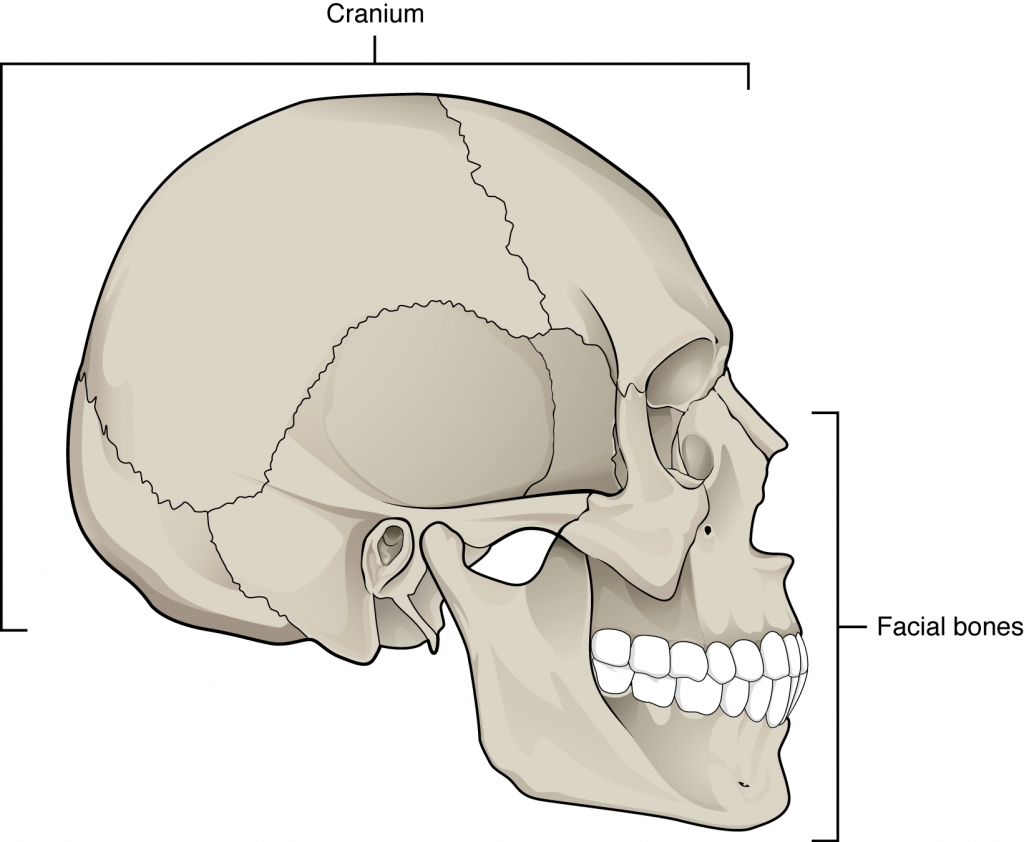

The skull is the skeletal structure of the head that supports the face and protects the brain. It is subdivided into the facial bones and the cranium, or cranial vault (see Figure 3.1). The facial bones underlie the facial structures, form the nasal cavity, enclose the eyeballs, and support the teeth of the upper and lower jaws. The rounded cranium surrounds and protects the brain and houses the middle and inner ear structures.

In the adult, the skull consists of 22 individual bones, 21 of which are immobile and united into a single unit. The 22nd bone is the mandible (lower jaw), which is the only moveable bone of the skull.

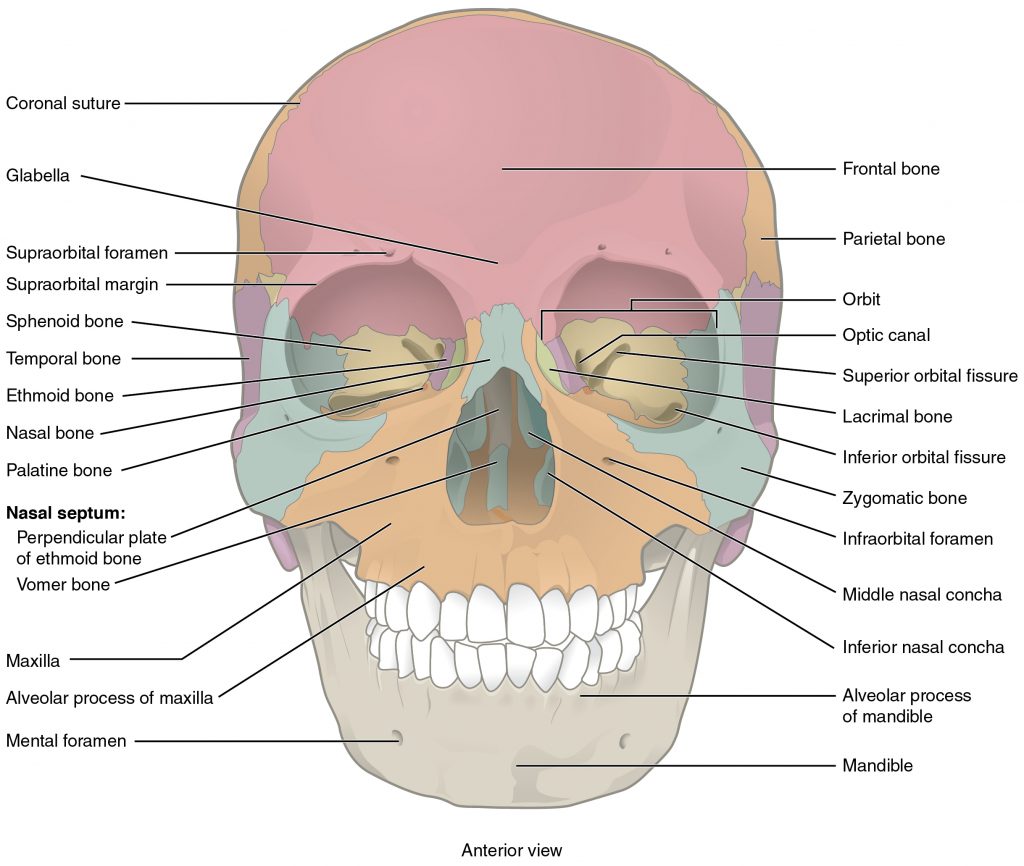

Anterior View of Skull

The anterior skull consists of the facial bones and provides the bony support for the eyes, teeth and structures of the face and provides openings for eating and breathing. This view of the skull is dominated by the openings of the orbits and the nasal cavity. Also seen are the upper and lower jaws, with their respective teeth (see Figure 3.2).

The orbit is the bony socket that houses the eyeball and muscles that move the eyeball or open the upper eyelid. The upper margin of the anterior orbit is the supraorbital margin. Located near the midpoint of the supraorbital margin is a small opening called the supraorbital foramen. This provides for passage of a sensory nerve to the skin of the forehead. Below the orbit is the infraorbital foramen, which is the point of emergence for a sensory nerve that supplies the anterior face below the orbit.

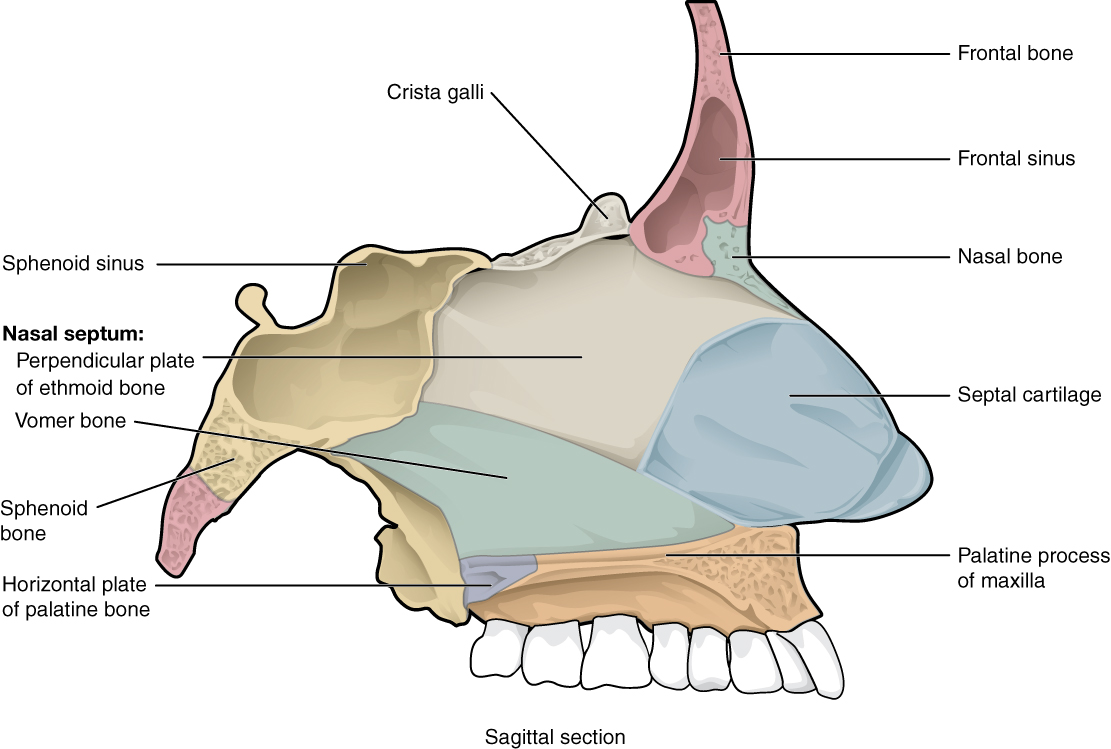

Inside the nasal area of the skull, the nasal cavity is divided into halves by the nasal septum. The upper portion of the nasal septum is formed by the perpendicular plate of the ethmoid bone and the lower portion is the vomer bone. When looking into the nasal cavity from the front of the skull, two bony plates are seen projecting from each lateral wall. The larger of these is the inferior nasal concha, an independent bone of the skull. Located just above the inferior concha is the middle nasal concha, which is part of the ethmoid bone. A third bony plate, also part of the ethmoid bone, is the superior nasal concha. It is much smaller and out of sight, above the middle concha. The superior nasal concha is located just lateral to the perpendicular plate, in the upper nasal cavity.

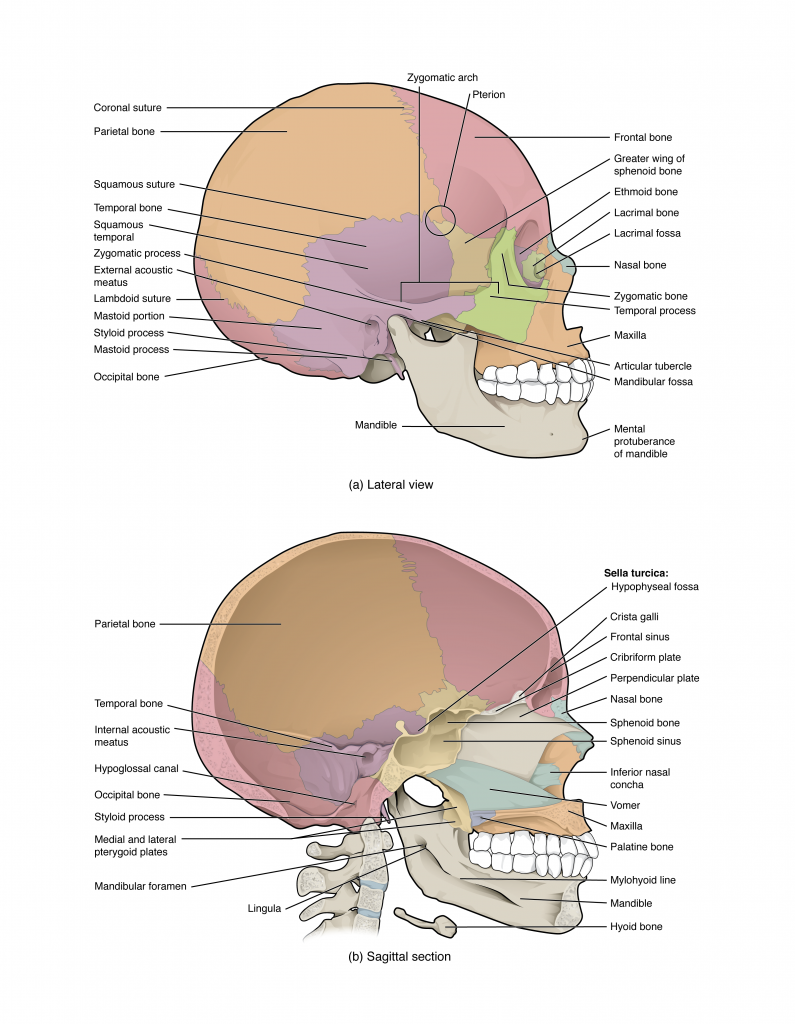

Lateral View of Skull

A view of the lateral skull is dominated by the large, rounded cranium above and the upper and lower jaws with their teeth below (see Figure 3.3). Separating these areas is the bridge of bone called the zygomatic arch. The zygomatic arch (cheekbone) is the bony arch on the side of skull that spans from the area of the cheek to just above the ear canal. It is formed by the junction of two bony processes: a short anterior component, the temporal process of the zygomatic bone and a longer posterior portion, the zygomatic process of the temporal bone, extending forward from the temporal bone. Thus the temporal process (anteriorly) and the zygomatic process (posteriorly) join together, like the two ends of a drawbridge, to form the zygomatic arch. One of the major muscles that pulls the mandible upward during biting and chewing, the masseter, arises from the zygomatic arch.

On the lateral side of the cranium, above the level of the zygomatic arch, is a shallow space called the temporal fossa. Arising from the temporal fossa and passing deep to the zygomatic arch is another muscle that acts on the mandible during chewing, the temporalis.

Bones of the Cranium

The cranium contains and protects the brain. The interior space that is almost completely occupied by the brain is called the cranial cavity. This cavity is bounded superiorly by the rounded top of the skull, which is called the calvaria (skullcap), and the lateral and posterior sides of the skull. The bones that form the top and sides of the cranium are usually referred to as the “flat” bones of the skull.

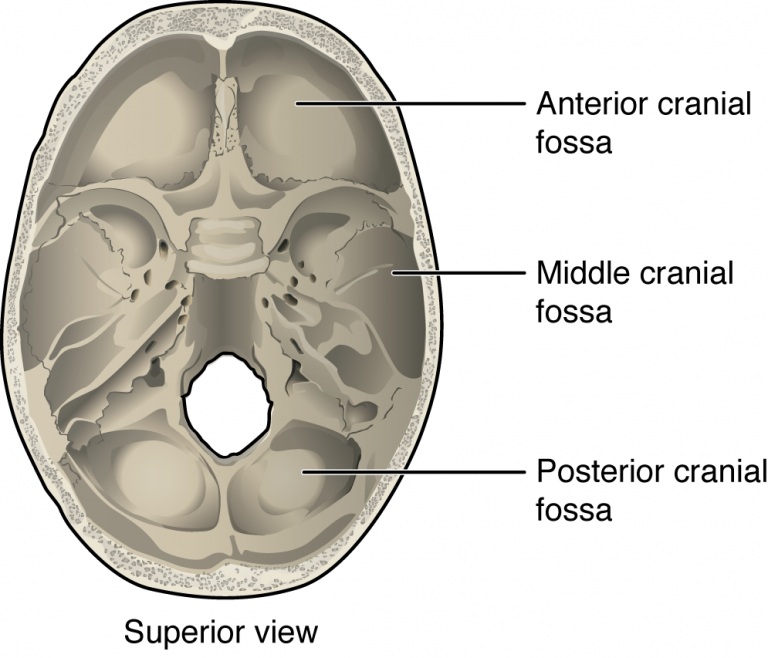

The floor of the brain case is referred to as the base of the skull or cranial floor. This is a complex area that varies in depth and has numerous openings for the passage of cranial nerves, blood vessels, and the spinal cord. Inside the skull, the base is subdivided into three large spaces, called the anterior cranial fossa, middle cranial fossa, and posterior cranial fossa (fossa = “trench or ditch”) (see Figure 3.4). From anterior to posterior, the fossae increase in depth. The shape and depth of each fossa correspond to the shape and size of the brain region that each houses.

The cranium consists of eight bones. These include the paired parietal and temporal bones, plus the unpaired frontal, occipital, sphenoid, and ethmoid bones.

Parietal Bone

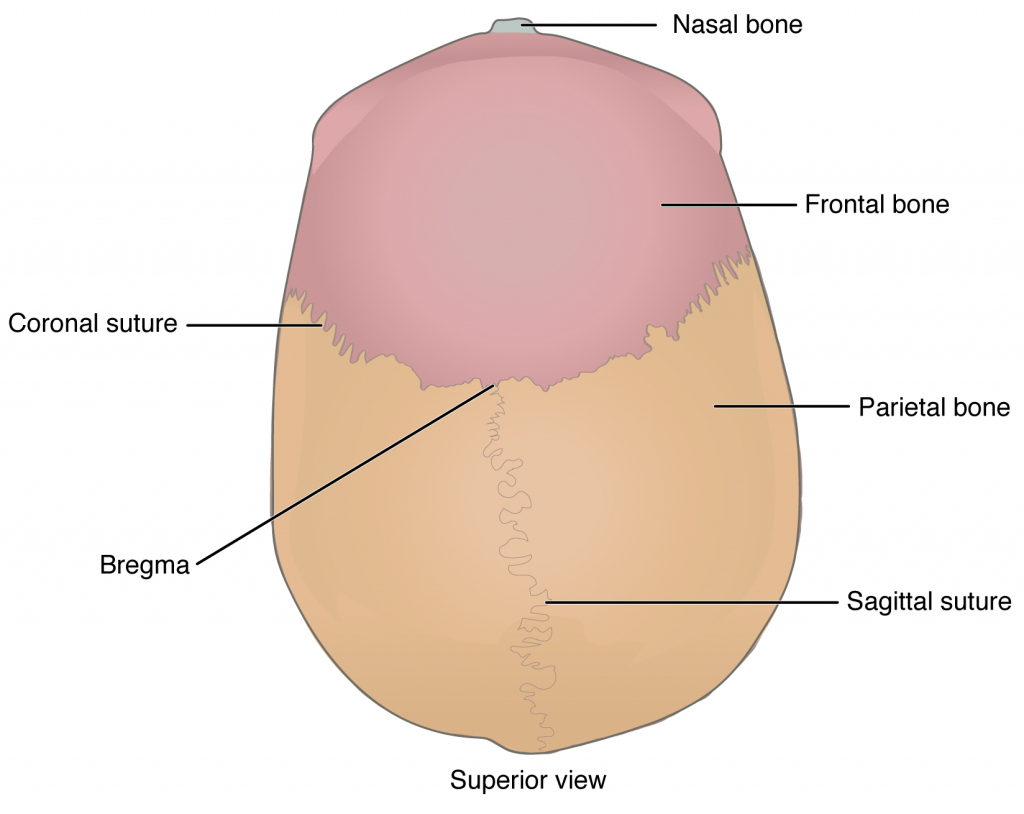

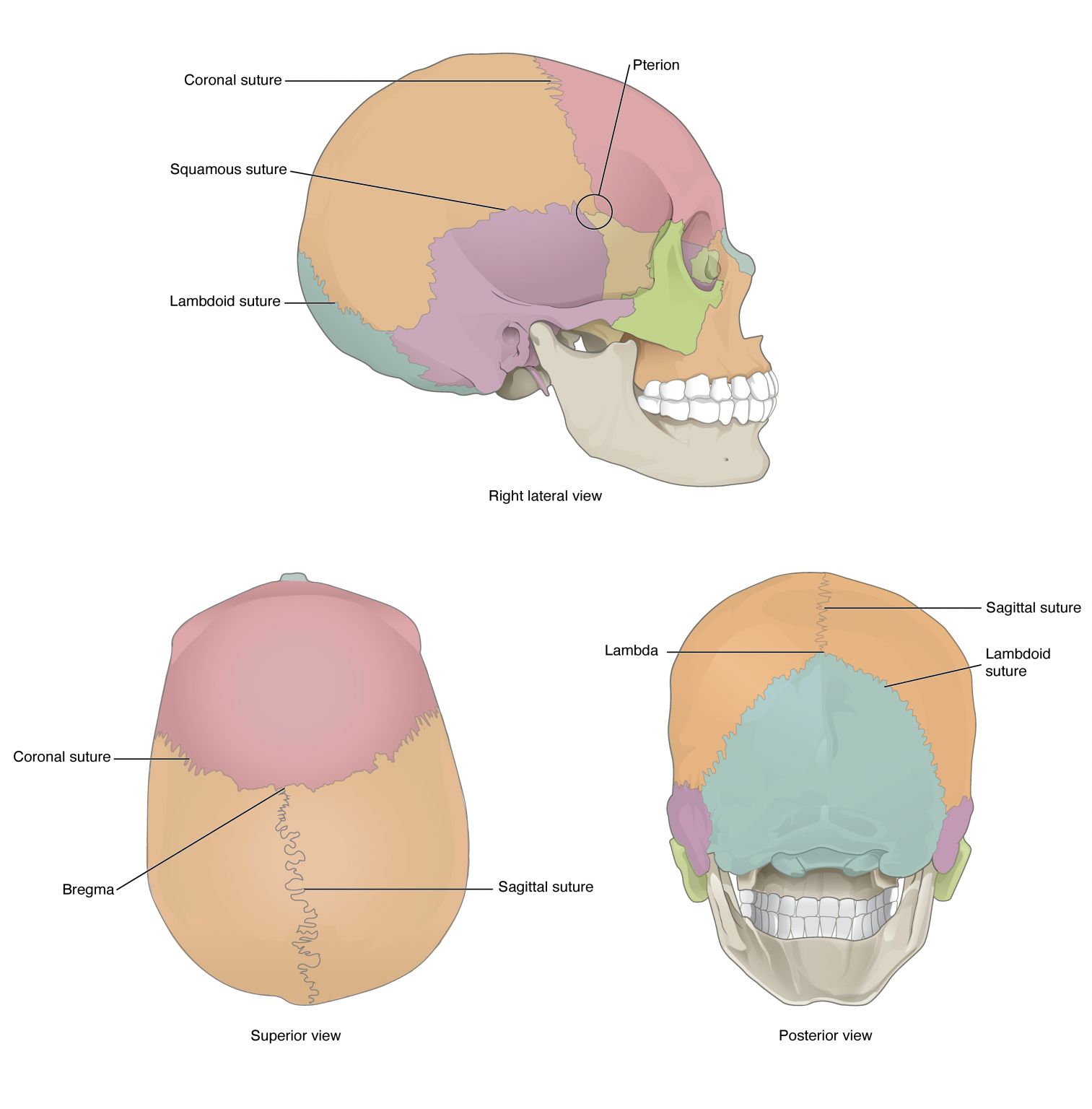

The parietal bone forms most of the upper and lateral side of the skull (see Figure 3.3). These are paired bones, with the right and left parietal bones joining together at the top of the skull forming the sagittal suture. Each parietal bone is also bounded anteriorly by the frontal bone at the coronal suture, inferiorly by the temporal bone at the squamous suture, and posteriorly by the occipital bone at the lambdoid suture.

Temporal Bone

The temporal bone forms the lower lateral side of the skull (see Figure 3.3). Common wisdom has it that the temporal bone (temporal = “time”) is so named because this area of the head (the temple) is where hair typically first turns gray, indicating the passage of time.

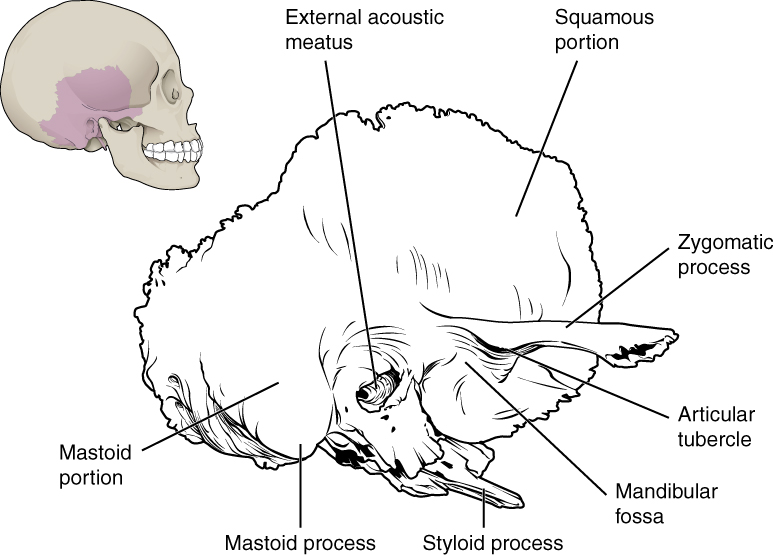

The temporal bone is subdivided into several regions (see Figure 3.6). The flattened, upper portion is the squamous portion of the temporal bone. Below this area and projecting anteriorly is the zygomatic process of the temporal bone, which forms the posterior portion of the zygomatic arch. Posteriorly is the mastoid portion of the temporal bone. Projecting inferiorly from this region is a large prominence, the mastoid process, which serves as a muscle attachment site. The mastoid process can easily be felt on the side of the head just behind your earlobe. On the interior of the skull, the petrous portion of each temporal bone forms the prominent, vertical, diagonally oriented petrous ridge which rises from the posterior cranial fossa to the middle cranial fossa. Located inside each petrous ridge are small cavities that house the structures of the middle and inner ears.

Important landmarks of the temporal bone, as shown in Figure 3.7, include the following:

- External acoustic meatus (ear canal): This is the large opening on the lateral side of the skull that is associated with the ear.

- Internal acoustic meatus: This opening is located inside the cranial cavity, on the medial side of the petrous ridge. It connects to the middle and inner ear cavities of the temporal bone.

- Mandibular fossa: This is the deep, oval-shaped depression located on the external base of the skull, just in front of the external acoustic meatus. The mandible (lower jaw) joins with the skull at this site as part of the temporomandibular joint, which allows for movements of the mandible during opening and closing of the mouth.

- Articular tubercle: The smooth ridge located immediately anterior to the mandibular fossa. Both the articular tubercle and mandibular fossa contribute to the temporomandibular joint, the joint that provides for movements between the temporal bone of the skull and the mandible.

- Styloid process: Posterior to the mandibular fossa on the external base of the skull is an elongated, downward bony projection called the styloid process, so named because of its resemblance to a stylus (a pen or writing tool). This structure serves as an attachment site for several small muscles and for a ligament that supports the hyoid bone of the neck. (see Figure 3.6)

- Stylomastoid foramen: This small opening is located between the styloid process and mastoid process. This is the point of exit for the cranial nerve that supplies the facial muscles.

- Carotid canal: The carotid canal is a zig-zag shaped tunnel that provides passage through the base of the skull for one of the major arteries that supplies the brain. Its entrance is located on the outside base of the skull, anteromedial to the styloid process and directly anterior to the jugular foramen. The canal then runs anteromedially within the bony base of the skull, and then turns upward to its exit in the floor of the middle cranial cavity, above the foramen lacerum.

- Jugular foramen: The opening in the temporal bone directly posterior to the carotid canal. The is the point of exit for the internal jugular vein.

Frontal Bone

The frontal bone is the single bone that forms the forehead. At its anterior midline, between the eyebrows, there is a slight depression called the glabella (see Figure 3.3). The frontal bone also forms the supraorbital margin of the orbit. Near the middle of this margin, is the supraorbital foramen, the opening that provides passage for a sensory nerve to the forehead. The frontal bone is thickened just above each supraorbital margin, forming rounded brow ridges. These are located just behind your eyebrows and vary in size among individuals, although they are generally larger in males. Inside the cranial cavity, the frontal bone extends posteriorly. This flattened region forms both the roof of the orbit below and the floor of the anterior cranial cavity above (see Figure 3.7b).

Occipital Bone

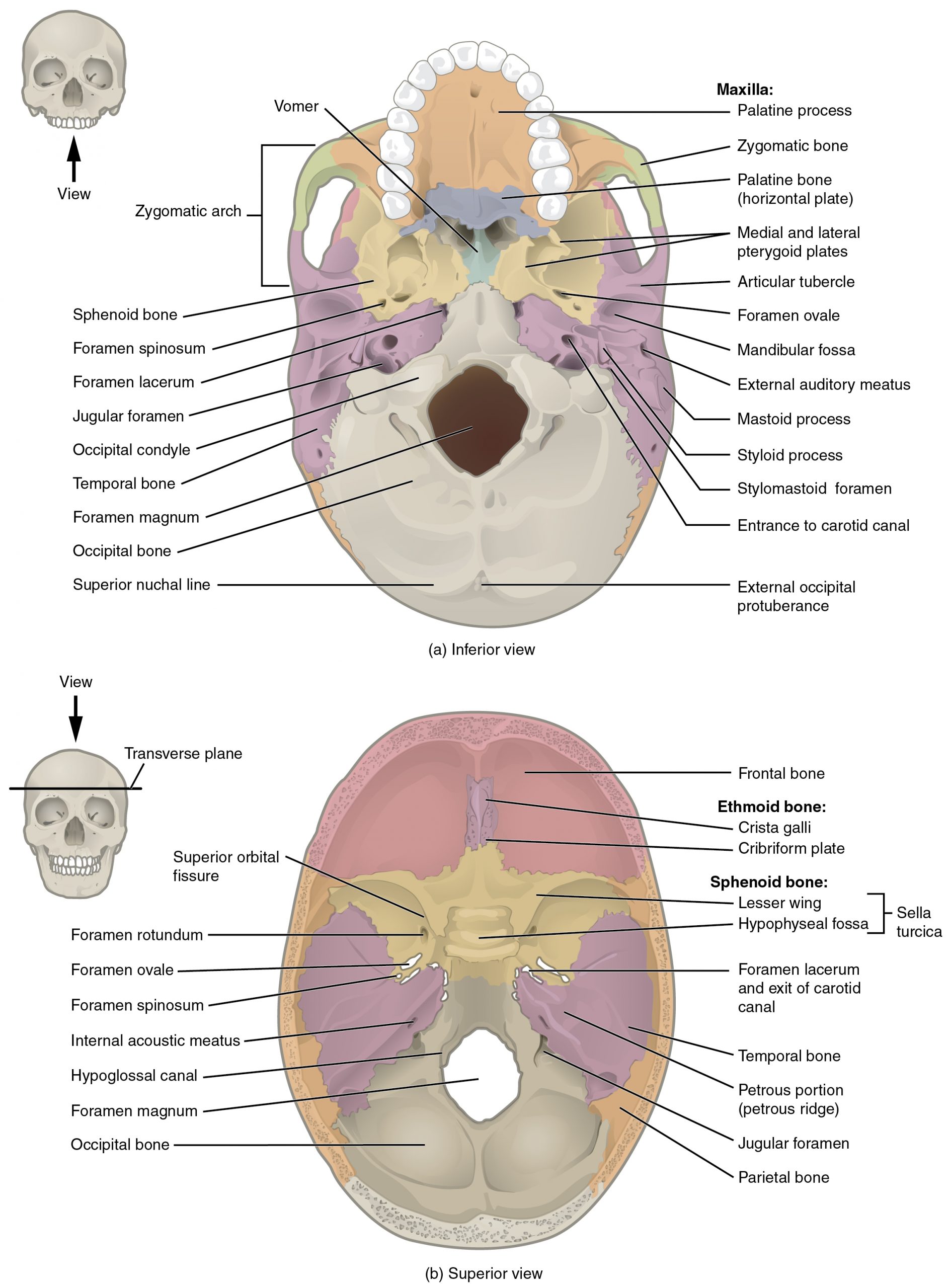

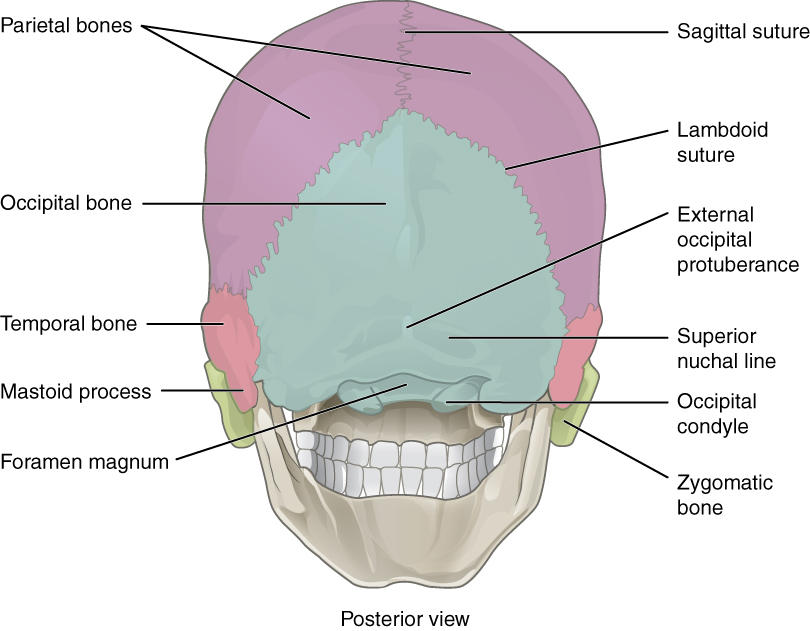

The occipital bone is the single bone that forms the posterior skull and posterior cranial fossa (see Figure 3.7; Figure 3.8). On its outside surface, at the posterior midline, is a small protrusion called the external occipital protuberance, which serves as an attachment site for a ligament of the posterior neck. Lateral to either side of this bump is a superior nuchal line (nuchal = “nape” or “posterior neck”). The nuchal lines represent the most superior point at which muscles of the neck attach to the skull, with only the scalp covering the skull above these lines. On the base of the skull, the occipital bone contains the large opening of the foramen magnum, which allows for passage of the spinal cord as it exits the skull. On either side of the foramen magnum is an oval-shaped occipital condyle. These condyles form joints with the first cervical vertebra which allow for the nodding (as in agreement) motion of the head.

Sphenoid Bone

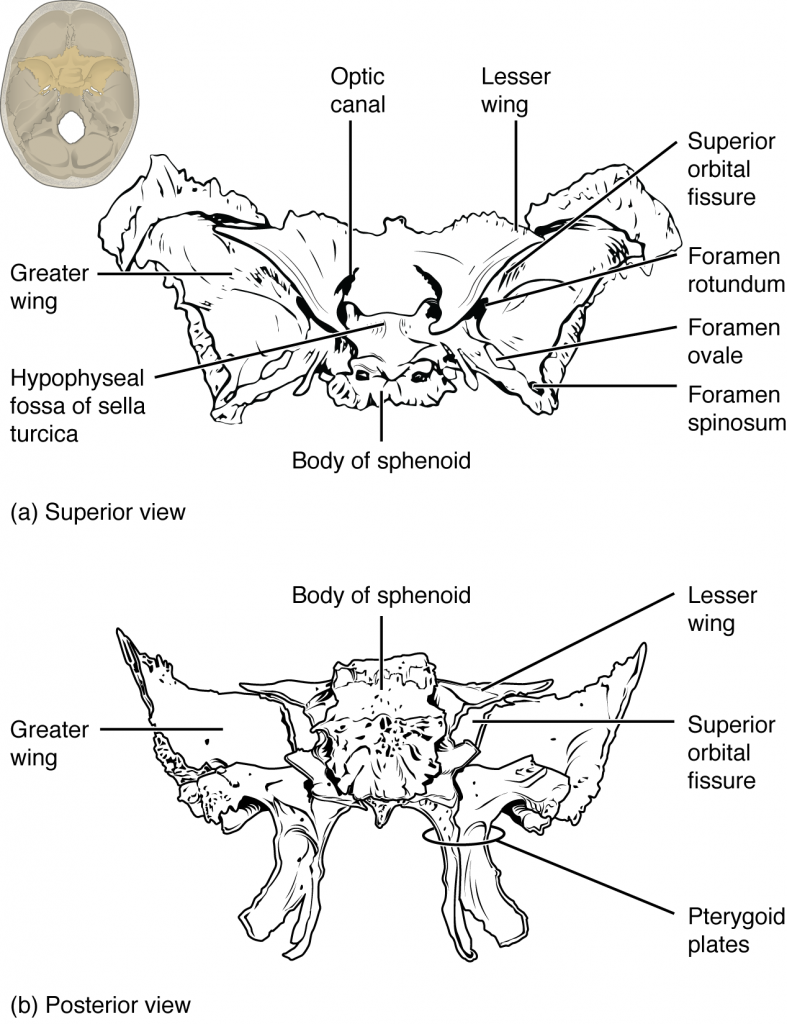

The sphenoid bone is a single, complex bone of the central skull (see Figure 3.9). It serves as a “keystone” bone, because it joins with almost every other bone of the skull. The sphenoid forms much of the base of the central skull (see Figure 3.7) and also extends laterally to contribute to the sides of the skull (see Figure 3.3). Inside the cranial cavity, the right and left lesser wings of the sphenoid bone, which resemble the wings of a flying bird, form the lip of a prominent ridge that marks the boundary between the anterior and middle cranial fossae. The sella turcica (“Turkish saddle”) is located at the midline of the middle cranial fossa. This bony region of the sphenoid bone is named for its resemblance to the horse saddles used by the Ottoman Turks, with a high back, called the dorsum sellae, and a tall front. The rounded depression in the floor of the sella turcica is the hypophyseal (pituitary) fossa, which houses the pea-sized pituitary (hypophyseal) gland. The greater wings of the sphenoid bone extend laterally to either side away from the sella turcica, where they form the anterior floor of the middle cranial fossa. The greater wing is best seen on the outside of the lateral skull, where it forms a rectangular area immediately anterior to the squamous portion of the temporal bone.

On the inferior aspect of the skull, each half of the sphenoid bone forms two thin, vertically oriented bony plates. These are the medial pterygoid plate and lateral pterygoid plate (pterygoid = “wing-shaped”). The right and left medial pterygoid plates form the posterior, lateral walls of the nasal cavity. The somewhat larger lateral pterygoid plates serve as attachment sites for chewing muscles that fill the infratemporal space and act on the mandible.

Important landmarks of the sphenoid, as shown in Figure 3.9.

- Optic canal: This opening is located at the anterior lateral corner of the sella turcica. It provides for passage of the optic nerve into the orbit.

- Superior orbital fissure: This large, irregular opening into the posterior orbit is located on the anterior wall of the middle cranial fossa, lateral to the optic canal and under the projecting margin of the lesser wing of the sphenoid bone. Nerves to the eyeball and associated muscles, and sensory nerves to the forehead pass through this opening.

- Foramen rotundum: This rounded opening (rotundum = “round”) is located in the floor of the middle cranial fossa, just inferior to the superior orbital fissure. It is the exit point for a major sensory nerve that supplies the cheek, nose, and upper teeth.

- Foramen ovale of the middle cranial fossa: This large, oval-shaped opening in the floor of the middle cranial fossa provides passage for a major sensory nerve to the lateral head, cheek, chin, and lower teeth.

- Foramen spinosum: This small opening, located posterior-lateral to the foramen ovale, is the entry point for an important artery that supplies the covering layers surrounding the brain. The branching pattern of this artery forms readily visible grooves on the internal surface of the skull and these grooves can be traced back to their origin at the foramen spinosum.

- Carotid canal: This is the zig-zag passageway through which a major artery to the brain enters the skull. The entrance to the carotid canal is located on the inferior aspect of the skull, anteromedial to the styloid process (see Figure 3.7a). From here, the canal runs anteromedially within the bony base of the skull. Just above the foramen lacerum, the carotid canal opens into the middle cranial cavity, near the posterior-lateral base of the sella turcica.

- Foramen lacerum: This irregular opening is located in the base of the skull, immediately inferior to the exit of the carotid canal. This opening is an artifact of the dry skull, because in life it is completely filled with cartilage. All the openings of the skull that provide for passage of nerves or blood vessels have smooth margins; the word lacerum (“ragged” or “torn”) tells us that this opening has ragged edges and thus nothing passes through it.

Ethmoid Bone

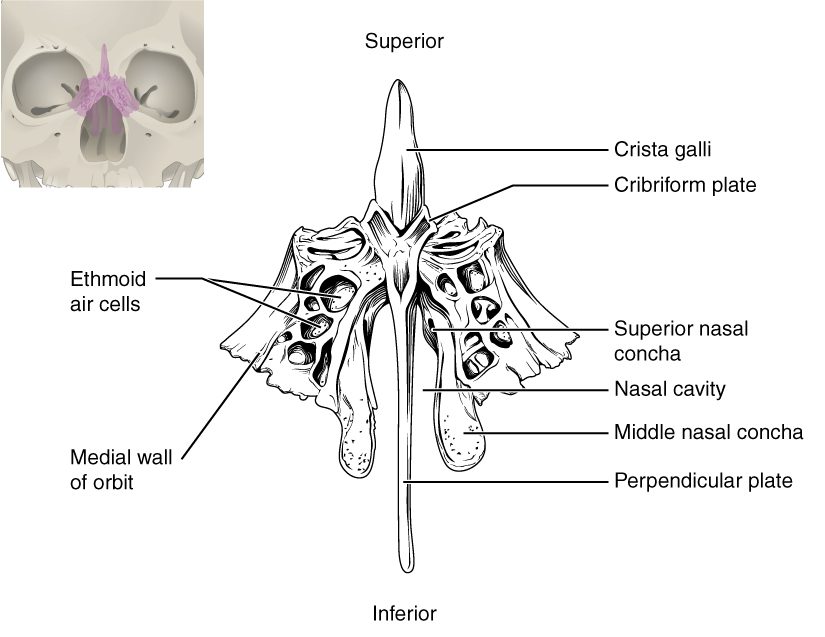

The ethmoid bone is a single, midline bone that forms the roof and lateral walls of the upper nasal cavity, the upper portion of the nasal septum, and contributes to the medial wall of the orbit (see Figure 3.10 and Figure 3.11). On the interior of the skull, the ethmoid also forms a portion of the floor of the anterior cranial cavity (see Figure 3.7b).

Within the nasal cavity, the perpendicular plate of the ethmoid bone forms the upper portion of the nasal septum. The ethmoid bone also forms the lateral walls of the upper nasal cavity. Extending from each lateral wall are the superior nasal concha and middle nasal concha, which are thin, curved projections (turbinates) that extend into the nasal cavity (see Figure 3.12).

In the cranial cavity, the ethmoid bone forms a small area at the midline in the floor of the anterior cranial fossa. This region also forms the narrow roof of the underlying nasal cavity. This portion of the ethmoid bone consists of two parts, the crista galli and cribriform plates. The crista galli (“rooster’s comb or crest”) is a small upward bony projection located at the midline. It functions as an anterior attachment point for one of the meninges (protective membranes covering the brain). To either side of the crista galli is the cribriform plate (cribrum = “sieve”), a small, flattened area with numerous small openings termed olfactory foramina. Small nerve branches from the olfactory areas of the nasal cavity pass through these openings to enter the brain.

The lateral portions of the ethmoid bone are located between the orbit and upper nasal cavity, and thus form the lateral nasal cavity wall and a portion of the medial orbit wall. Located inside this portion of the ethmoid bone are several small, air-filled spaces that are part of the paranasal sinus system of the skull.

Sutures of the Skull

A suture is an immobile joint between adjacent bones of the skull. The narrow gap between the bones is filled with dense, fibrous connective tissue that unites the bones. The long sutures located between the bones of the cranium are not straight, but instead follow irregular, tightly twisting paths. These twisting lines serve to tightly interlock the adjacent bones, thus adding strength to the skull to protect the brain.

The two suture lines seen on the top of the skull are the coronal and sagittal sutures. The coronal suture runs from side to side across the skull, within the coronal plane of section (see Figure 3.3). It joins the frontal bone to the right and left parietal bones. The sagittal suture extends posteriorly from the coronal suture at the intersection called bregma, running along the midline at the top of the skull in the sagittal plane of section (see Figure 3.8). It unites the right and left parietal bones. On the posterior skull, the sagittal suture terminates by joining the lambdoid suture at the intersection called lambda. The lambdoid suture extends downward and laterally to either side away from its junction with the sagittal suture. The lambdoid suture joins the occipital bone to the right and left parietal and temporal bones. This suture is named for its upside-down “V” shape, which resembles the capital letter version of the Greek letter lambda (Λ). The squamous suture is located on the lateral skull. It unites the squamous portion of the temporal bone with the parietal bone (see Figure 3.3). At the intersection of the frontal bone, parietal bone, squamous portion of the temporal bone, and greater wing of the sphenoid bone is the pterion, a small, capital-H-shaped suture line that unites the region. It is the weakest part of the skull. The pterion is located approximately two finger widths above the zygomatic arch and a thumb’s width posterior to the upward portion of the zygomatic bone.

Facial Bones of the Skull

The facial bones of the skull form the upper and lower jaws, the nose, nasal cavity and nasal septum, and the orbit. The facial bones include 14 bones, with six paired bones and two unpaired bones. The paired bones are the maxilla, palatine, zygomatic, nasal, lacrimal, and inferior nasal conchae bones. The unpaired bones are the vomer and mandible bones. Although classified with the cranial bones, the ethmoid bone also contributes to the nasal septum and the walls of the nasal cavity and orbit.

Maxillary Bone

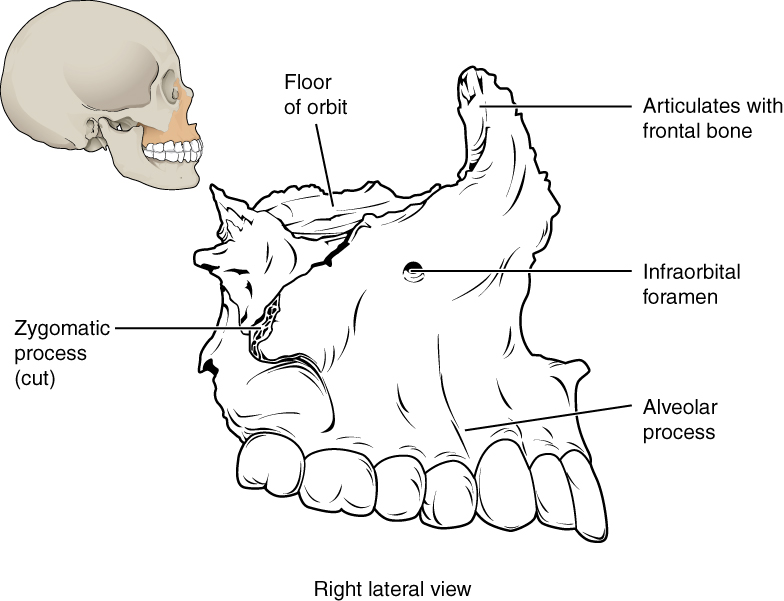

The maxillary bone, often referred to simply as the maxilla (plural = maxillae), is one of a pair that together form the upper jaw, much of the hard palate, the medial floor of the orbit, and the lateral base of the nose (see Figure 3.2). The curved, inferior margin of the maxillary bone that forms the upper jaw and contains the upper teeth is the alveolar process of the maxilla (see Figure 3.13). Each tooth is anchored into a deep socket called an alveolus. On the anterior maxilla, just below the orbit, is the infraorbital foramen. This is the point of exit for a sensory nerve that supplies the nose, upper lip, and anterior cheek. On the inferior skull, the palatine process from each maxillary bone can be seen joining together at the midline to form the anterior three-quarters of the hard palate (see Figure 3.7a). The hard palate is the bony plate that forms the roof of the mouth and floor of the nasal cavity, separating the oral and nasal cavities.

Palatine Bone

The palatine bone is one of a pair of irregularly shaped bones that contribute small areas to the lateral walls of the nasal cavity and the medial wall of each orbit. The largest region of each of the palatine bone is the horizontal plate. The plates from the right and left palatine bones join together at the midline to form the posterior quarter of the hard palate (see Figure 3.7a). Thus, the palatine bones are best seen in an inferior view of the skull and hard palate.

Zygomatic Bone

The zygomatic bone is also known as the cheekbone. Each of the paired zygomatic bones forms much of the lateral wall of the orbit and the lateral-inferior margins of the anterior orbital opening (see Figure 3.2). The short temporal process of the zygomatic bone projects posteriorly, where it forms the anterior portion of the zygomatic arch (see Figure 3.3).

Nasal Bone

The nasal bone is one of two small bones that articulate with each other to form the bony base (bridge) of the nose. They also support the cartilages that form the lateral walls of the nose (see Figure 3.10). These are the bones that are damaged when the nose is broken.

Lacrimal Bone

Each lacrimal bone is a small, rectangular bone that forms the anterioromedial wall of the orbit (see Figure 3.2 and Figure 3.3). The anterior portion of the lacrimal bone forms a shallow depression called the lacrimal fossa, and extending inferiorly from this is the nasolacrimal canal. The lacrimal fluid (tears of the eye), which serves to maintain the moist surface of the eye, drains at the medial corner of the eye into the nasolacrimal canal. This duct then extends downward to open into the nasal cavity, behind the inferior nasal concha. In the nasal cavity, the lacrimal fluid normally drains posteriorly, but with an increased flow of tears due to crying or eye irritation, some fluid will also drain anteriorly, thus causing a runny nose.

Inferior Nasal Conchae

The right and left inferior nasal conchae form a curved bony plate (turbinate) that projects into the nasal cavity space from the lower lateral wall (see Figure 3.12). The inferior concha is the largest of the nasal conchae and can easily be seen when looking into the anterior opening of the nasal cavity.

Vomer Bone

The unpaired vomer bone, often referred to simply as the vomer, is triangular-shaped and forms the posterior-inferior part of the nasal septum (see Figure 3.10). The vomer is best seen when looking from behind into the posterior openings of the nasal cavity (see Figure 3.7a). In this view, the vomer is seen to form the entire height of the nasal septum. A much smaller portion of the vomer can also be seen when looking into the anterior opening of the nasal cavity.

Mandible

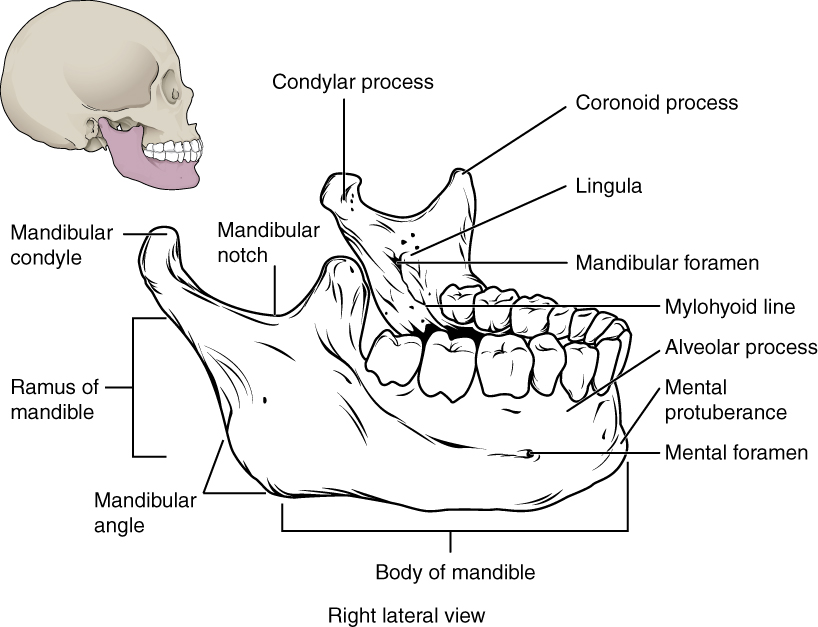

The mandible forms the lower jaw and is the only moveable bone of the skull. At the time of birth, the mandible consists of paired right and left bones, but these fuse together during the first year to form the single U-shaped mandible of the adult skull. Each side of the mandible consists of a horizontal body and posteriorly, a vertically oriented ramus of the mandible (ramus = “branch”). The outside margin of the mandible, where the body and ramus come together is called the angle of the mandible (see Figure 3.14).

The ramus on each side of the mandible has two upward-going bony projections. The more anterior projection is the flattened coronoid process of the mandible, which provides attachment for one of the biting muscles. The posterior projection is the mandibular condyles, which is topped by the oval-shaped condyle. The condyle of the mandible articulates (joins) with the mandibular fossa and articular tubercle of the temporal bone. Together these articulations form the temporomandibular joint, which allows for opening and closing of the mouth (see Figure 3.3). The broad U-shaped curve located between the coronoid and condylar processes is the mandibular notch.

Important landmarks for the mandible include the following:

- Alveolar process of the mandible: This is the upper border of the mandibular body and serves to anchor the lower teeth.

- Mental protuberance: The forward projection from the inferior margin of the anterior mandible that forms the chin (mental = “chin”).

- Mental foramen: The opening located on each side of the anterior-lateral mandible, which is the exit site for a sensory nerve that supplies the chin.

- Mylohyoid line: This bony ridge extends along the inner aspect of the mandibular body (see Figure 3.10). The muscle that forms the floor of the oral cavity attaches to the mylohyoid lines on both sides of the mandible.

- Mandibular foramen: This opening is located on the medial side of the ramus of the mandible. The opening leads into a tunnel that runs down the length of the mandibular body. The sensory nerve and blood vessels that supply the lower teeth enter the mandibular foramen and then follow this tunnel. Thus, to numb the lower teeth prior to dental work, the dentist must inject anesthesia into the lateral wall of the oral cavity at a point prior to where this sensory nerve enters the mandibular foramen.

- Lingula: This small flap of bone is named for its shape (lingula = “little tongue”). It is located immediately next to the mandibular foramen, on the medial side of the ramus. A ligament that anchors the mandible during opening and closing of the mouth extends down from the base of the skull and attaches to the lingula.

The Orbit

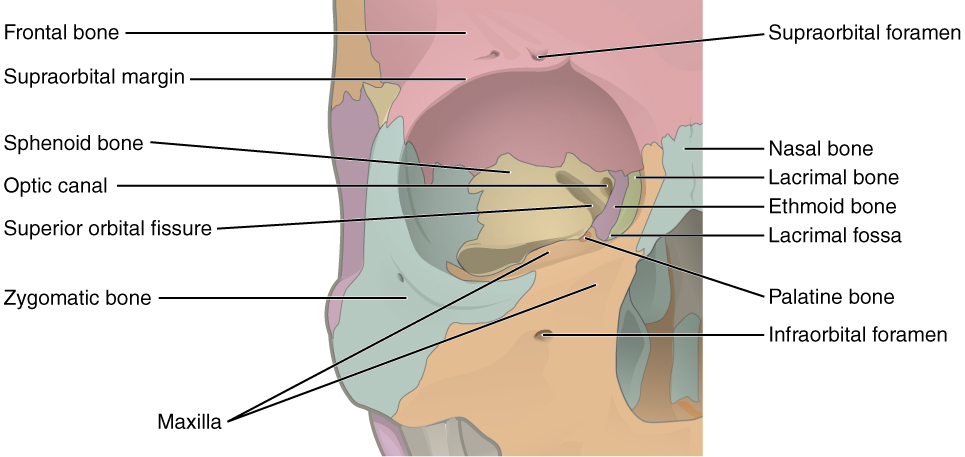

The orbit is the bony socket that houses the eyeball and contains the muscles that move the eyeball or open the upper eyelid. Each orbit is cone-shaped, with a narrow posterior region that widens toward the large anterior opening. To help protect the eye, the bony margins of the anterior opening are thickened and somewhat constricted. The medial walls of the two orbits are parallel to each other but each lateral wall diverges away from the midline at a 45° angle. This divergence provides greater lateral peripheral vision.

The walls of each orbit include contributions from seven skull bones (see Figure 3.15). The frontal bone forms the roof and the zygomatic bone forms the lateral wall and lateral floor. The medial floor is primarily formed by the maxilla, with a small contribution from the palatine bone. The ethmoid bone and lacrimal bone make up much of the medial wall and the sphenoid bone forms the posterior orbit.

At the posterior apex of the orbit is the opening of the optic canal, which allows for passage of the optic nerve from the retina to the brain. Lateral to this is the elongated and irregularly shaped superior orbital fissure, which provides passage for the artery that supplies the eyeball, sensory nerves, and the nerves that supply the muscles involved in eye movements.

The Nasal Septum and Nasal Conchae

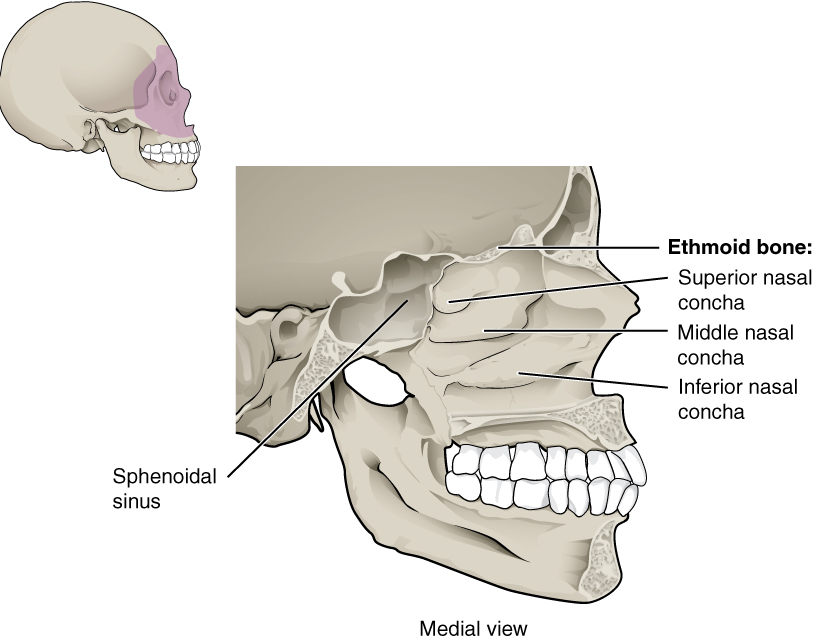

The nasal septum consists of both bone and cartilage components (see Figure 3.10 and Figure 3.16). The upper portion of the septum is formed by the perpendicular plate of the ethmoid bone. The lower and posterior parts of the septum are formed by the triangular-shaped vomer bone. The anterior nasal septum is formed by the septal cartilage, a flexible plate that fills in the gap between the perpendicular plate of the ethmoid and vomer bones. This cartilage also extends outward into the nose where it separates the right and left nostrils. Attached to the lateral wall on each side of the nasal cavity are the superior, middle, and inferior nasal conchae (singular = concha), which are named for their positions (see Figure 7.3.12). These are bony plates that curve downward as they project into the space of the nasal cavity. They serve to swirl the incoming air, which helps to warm and moisturize it before the air moves into the delicate air sacs of the lungs. This also allows mucus, secreted by the tissue lining the nasal cavity, to trap incoming dust, pollen, bacteria, and viruses. The largest of the conchae are the inferior nasal conchae, which is an independent bone of the skull. The middle conchae and the superior conchae, which are the smallest, are all formed by the ethmoid bone. When looking into the anterior nasal opening of the skull, only the inferior and middle conchae can be seen. The small superior nasal conchae are well hidden above and behind the middle conchae.

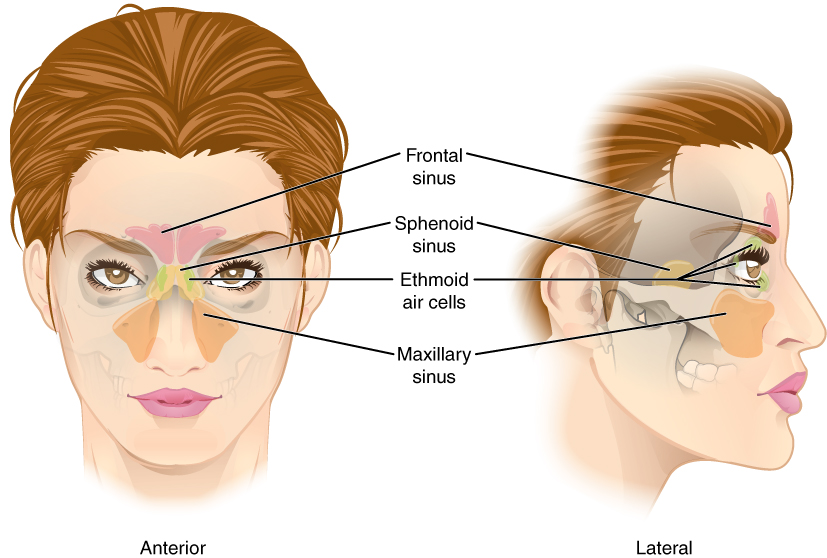

Paranasal Sinuses

The paranasal sinuses are hollow, air-filled spaces located within certain bones of the skull (see Figure 3.17). All of the sinuses communicate with the nasal cavity (paranasal = “next to nasal cavity”) and are lined with nasal mucosa. They serve to reduce bone mass and thus lighten the skull, and they also add resonance to the voice. This second feature is most obvious when you have a cold or sinus congestion which causes swelling of the mucosa and excess mucus production, obstructing the narrow passageways between the sinuses and the nasal cavity and causing your voice to sound different to yourself and others. This blockage can also allow the sinuses to fill with fluid, with the resulting pressure producing pain and discomfort.

The paranasal sinuses are named for the skull bone that each occupies. The frontal sinus is located just above the eyebrows, within the frontal bone (see Figure 7.3.16). This irregular space may be divided at the midline into bilateral spaces, or these may be fused into a single sinus space. The frontal sinus is the most anterior of the paranasal sinuses. The largest sinus is the maxillary sinus. These are paired and located within the right and left maxillary bones, where they occupy the area just below the orbits. The maxillary sinuses are most commonly involved during sinus infections. Because their connection to the nasal cavity is located high on their medial wall, they are difficult to drain. The sphenoid sinus is a single, midline sinus. It is located within the body of the sphenoid bone, just anterior and inferior to the sella turcica, thus making it the most posterior of the paranasal sinuses. The lateral aspects of the ethmoid bone contain multiple small spaces separated by very thin bony walls. Each of these spaces is called an ethmoid air cell. These are located on both sides of the ethmoid bone, between the upper nasal cavity and medial orbit, just behind the superior nasal conchae.

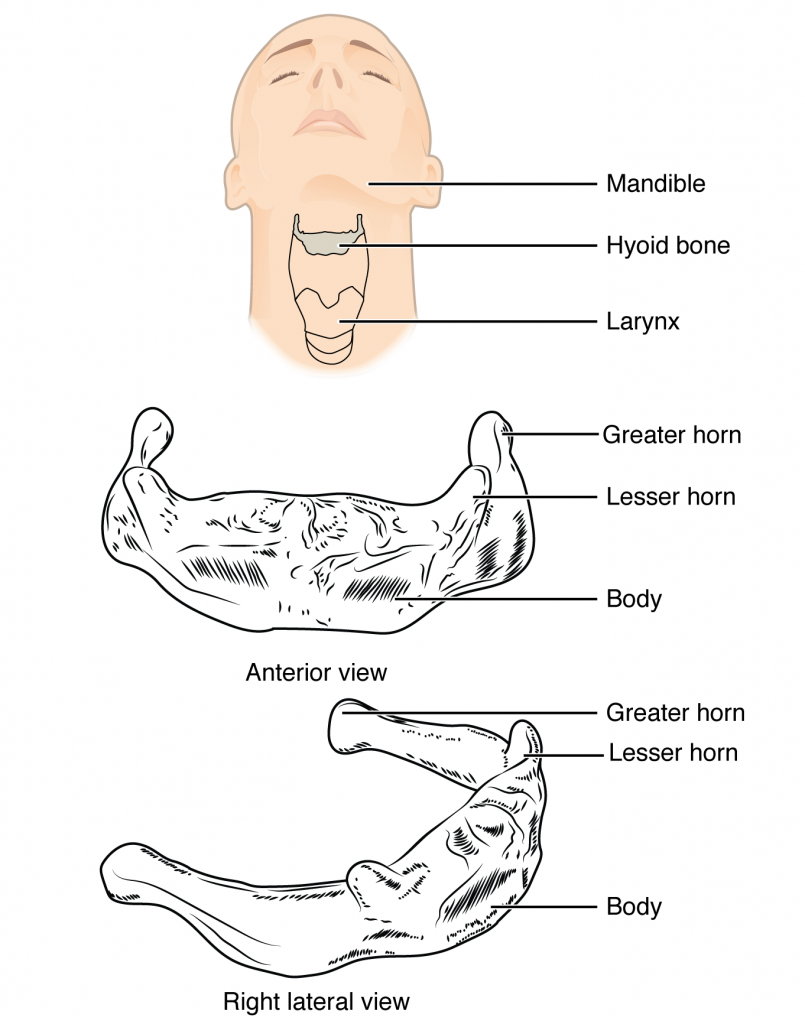

Hyoid Bone

The hyoid bone is an independent bone that does not contact any other bone and thus is not part of the skull (see Figure 3.18). It is a small U-shaped bone located in the upper neck near the level of the inferior mandible, with the tips of the “U” pointing posteriorly. The hyoid serves as the base for the tongue above, and is attached to the larynx below and the pharynx posteriorly. The hyoid is held in position by a series of small muscles that attach to it either from above or below. These muscles act to move the hyoid up/down or forward/back. Movements of the hyoid are coordinated with movements of the tongue, larynx, and pharynx during swallowing and speaking.